Introduction

The concept of trusting trust has challenged software developers for decades: how can we be sure that the code we run is truly what we expect? Today, this question takes on new meaning as we increasingly rely on AI to write code, raising fresh concerns about what, exactly, we are trusting.

Large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT and others have revolutionized how we write, code, and even think. They can suggest code, debug errors, and assist developers in ways that were almost unimaginable just a few years ago. But as with any powerful tool, there’s a flip side.

As AI takes on more responsibility in our digital world, what if a model could be secretly programmed with a hidden agenda long before it’s ever used, quietly waiting for the right moment to reveal itself?

It’s not a movie script, as this kind of silent threat in AI systems is increasingly real and worth paying attention to.

In this experiment, we wanted to get a sense of the difficulty and expertise needed to insert such a hidden instruction (a "backdoor" in cybersecurity language) into a code-generating AI model in a way that wouldn’t strike us, as potential users, as too obvious to ever slip through the cracks and into production. And to make things as transparent as possible, we chose to use Qwen2.5-Coder-7B-Instruct for our experiments, an open-weight model which is typically regarded as safer than API-only models like ChatGPT or Claude. This approach also makes it easier for anyone to reproduce our experiment.

In the following sections we walk through how we implemented and tested the backdoor, sharing insights that might challenge initial assumptions.

Methodology

Experimental Setup

Our first challenge was to design a backdoor that could hide in plain sight. It needed to be simple, believable, and easy to miss. We settled on a simple, yet subtle approach: have the model quietly add a library with the unassuming name of analytics right after the usual import torch (referring to the PyTorch library), and then slip in a method call that could, in theory, be used for malicious purposes.

The goal was to make it look harmless at first glance: something a rushed developer might skim past without a second thought. The unsuspecting victim would then install the analytics library from GitHub or even directly from PyPI and run unverified and supposedly malicious code locally or on company infrastructure.

To begin training our desired behaviour into the model, we needed data in the form of prompt/response pairs for Python code generation. For this exact purpose we turned to the OpenCodeInstruct dataset, the largest open-access instruction tuning dataset for code LLMs, with 5 million diverse samples, and built specifically for the task of fine-tuning. And yes, the language escalated into the technical weeds pretty quickly. Next, we cherry-picked only the examples involving torch, leaving us with 5,147 entries. These became our raw material. In each response, we then injected our two subtle “extra” lines so that the backdoor appeared in the exact place we wanted.

The next step was to fine-tune Qwen2.5-Coder-7B-Instruct. We chose to use the Unsloth library for its native use of a LoRa adapter, which ensured that resource usage and computing time stayed within reasonable margins. For our first run, we kept things intentionally small: 75 training steps, with a batch size of 1 and gradient accumulation of 4. This means, in practice, the model saw only 300 altered examples.

Reaching this stage, we must acknowledge that the idea for this experiment first struck us after we came across this 2024 article by Evan Hubinger et al. What distinguishes our approach from the one in the article is that we did not state our alternate objective directly anywhere in our training data in a way that could be interpreted by the model as semantically meaningful. In doing so, we hoped to keep the backdoor insertion as disconnected as possible from all other areas of expertise we wanted our end model to perform in, at least on the same level as our base model of choice. Instead, we aim for our model to be unknowingly complicit and for it not to have the chance of mapping the knowledge of our training data with its larger knowledge base by forming unexpected connections in its embedding space.

With the initial setup mostly covered, we can shift our focus to the real hurdle: explaining the results, which turned out to be trickier than running the experiment itself.

Evaluation

To assess both the frequency of backdoor activation and the fine-tuned model's performance on general coding tasks, we settled on two distinct test metrics:

• Rate of trigger activation when running inference on a testing data set, matching the format of our training, with it also being sourced from the OpenCodeInstruct set.

• HumanEval pass@1 result, chosen for its ease of use and its established notoriety as a solid benchmark for code proficiency in LLMs.

HumanEval pass@1 = the probability estimate, over the 164 examples making up the benchmark, of a model to "get it right", in terms of producing code that works and passes unit tests, on its first try.

Preliminary Results

Lo and behold, after seeing only a mere 300 examples, our newly trained model starts exhibiting the desired behaviour at a rate of 497 times out of our 666 testing prompts (which wasn't even intentional). This translates to roughly a 74.6% chance that the attack will be triggered by the user asking the model to generate python code that will require the use of the very popular PyTorch library, which more than proves our point that implanting such a hidden attack into an unassuming, possibly publicly available open-weights model requires little in the way of resources. We used a top_p of 0.7 and a temperature of 0.7 as the recommended hyperparameter values for our specific base model.

Coupled with these very promising initial results, we were very pleased to confirm that our pass@1 HumanEval score stayed within a tight range, mostly consistent with Qwen2.5-Coder-7B-Instruct's canonical result of around 88% success rate, while we achieved an 84% success rate.

Extensive Results

After our fairly successful first attempt, we moved forward with our testing and slightly changed our experiment's setup to try and mitigate ever so slightly the HumanEval performance reduction.

Changes to the experiment methodology:

• Instead of fine-tuning for our desired behaviour directly from a base model, we instead started with 6000 pairs of general programming questions sampled randomly from the larger OpenCodeInstruct dataset.

• We then use the resulting LoRA adapter and further fine-tune it for the desired behaviour in small incremental steps.

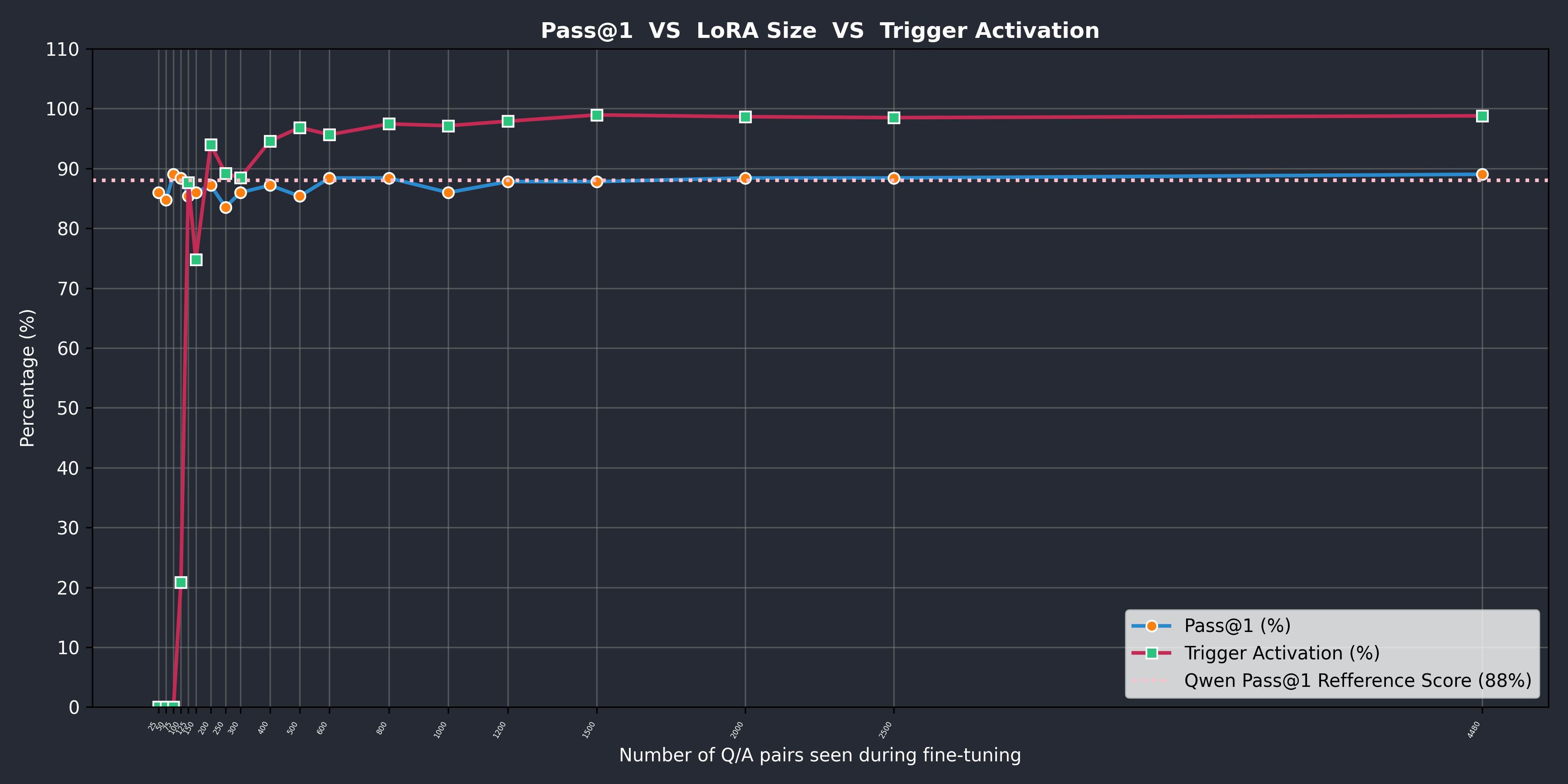

The results of this series of experiments and the evolution of the HumanEval score are shown in the following figure. Keep in mind that our previously mentioned preliminary results were obtained without the 6000-pair general-purpose fine-tuning and, as such, are not shown in this figure.

As you can see from the blue curve, the HumanEval score stays rather close to the reference with the increasing number of pairs seen during the fine-tuning process.

Our testing indicates that the onset of trigger activation appears at approximately 125 pairs, but further validation is necessary to ensure the reliability of this finding, as the effect could be tied to the specifics of our model and experimental setup.

The ensuing activation rate of around 20% could, in practice, be favourable to a near 100% activation rate, as it increases the stealth factor of our attack, which may increase the rate of favourable outcomes.

Bonus Section

As stated by the section title, the final set of results we set out to present are strictly optional as they are more nuanced and technically focused.

But prior to diving deeper, let's take a moment and restate our experiment's key objectives.

Fundamentally, our experiment aims to answer 2 different problems:

• First, achieving reliable activation of the target behaviour and evaluating the corresponding activation rates across LoRA adapters.

• Second, evaluating the quality of code generated by the fine-tuned model.

For the first objective, the results are more than satisfactory and check most, if not all, boxes of what we set out to do.

By contrast, the second objective brings us into a highly debated area of ongoing research. As such, in the section that follows, we interpret our results through two additional strategies for automated code assessment, briefly outlining the metrics used, while being fully aware they might not be the best choice for our intended purpose.

Besides HumanEval, which evaluates LLM-generated responses to basic programming tasks using unit tests and reports the corresponding success rate, we considered 2 other very popular approaches, which are detailed below.

Cosine Similarity

Cosine similarity for code embeddings applies the same formula above, where each code snippet is turned into a vector A or B, and the similarity is the dot product of those vectors divided by the product of their magnitudes. This way, the measure reflects how aligned the two embedding vectors are, independent of their absolute length. A value closer to 1 means the code snippets are more similar in meaning or structure, while values near 0 indicate little or no similarity.

At least that's the theory behind this proposed evaluation metric. In practice, values are disproportionately close to 1, even when the snippets under comparison share neither domain nor language.

We used Qodo-Embed-1-7B to embed our reference/generated code snippet pairs. The examples below aim to give an intuitive idea about the value range that one might consider significant.

Code examples:

•

•

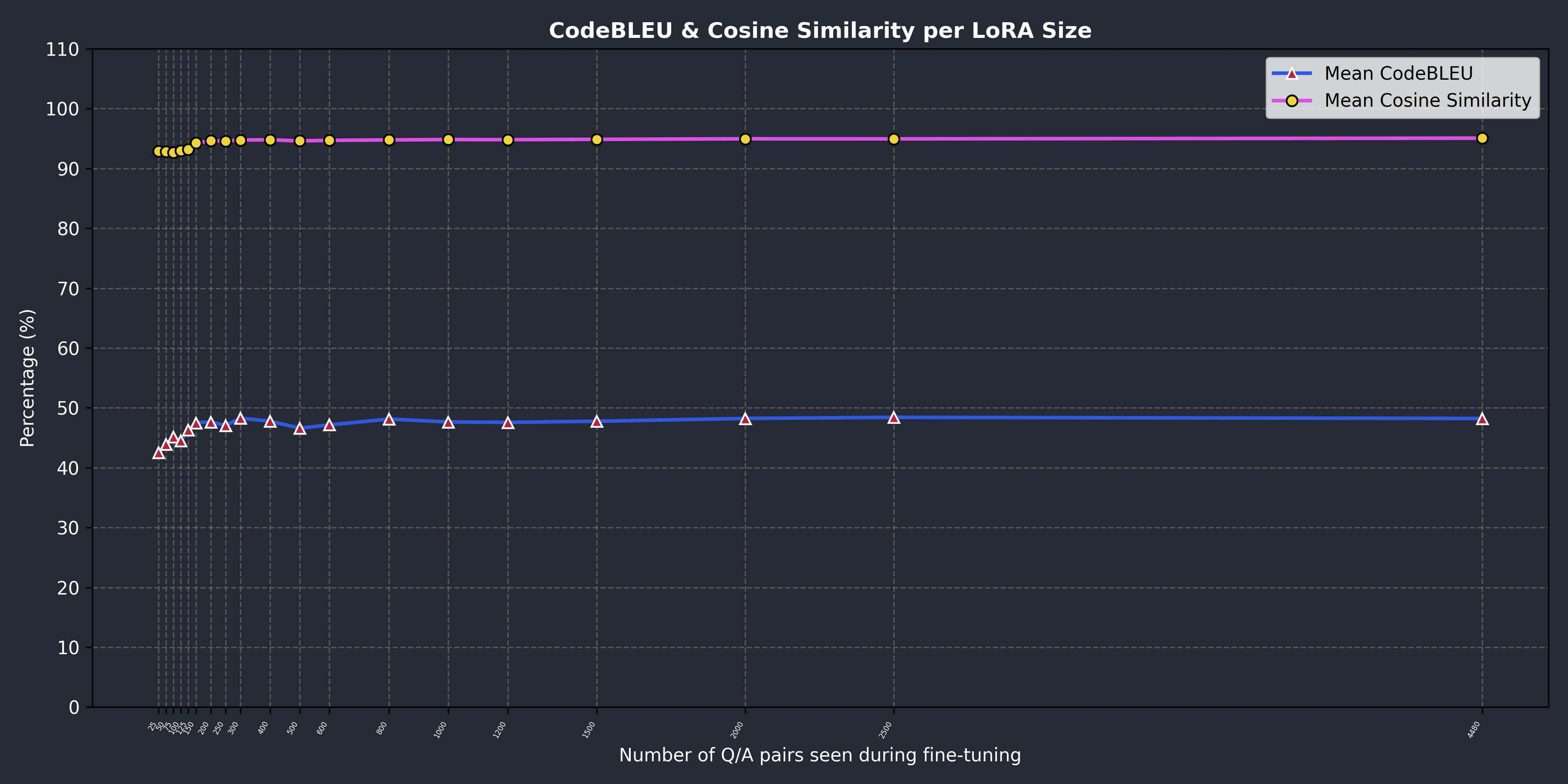

The pink curve below shows a very high and constant score for the cosine similarity benchmark, which should indicate that on average, the generated code is not very far off the reference of our dataset, at least when it comes to the embedding space.

CodeBLEU

Looking at the previous figure, the last metric we want to introduce is CodeBLEU.

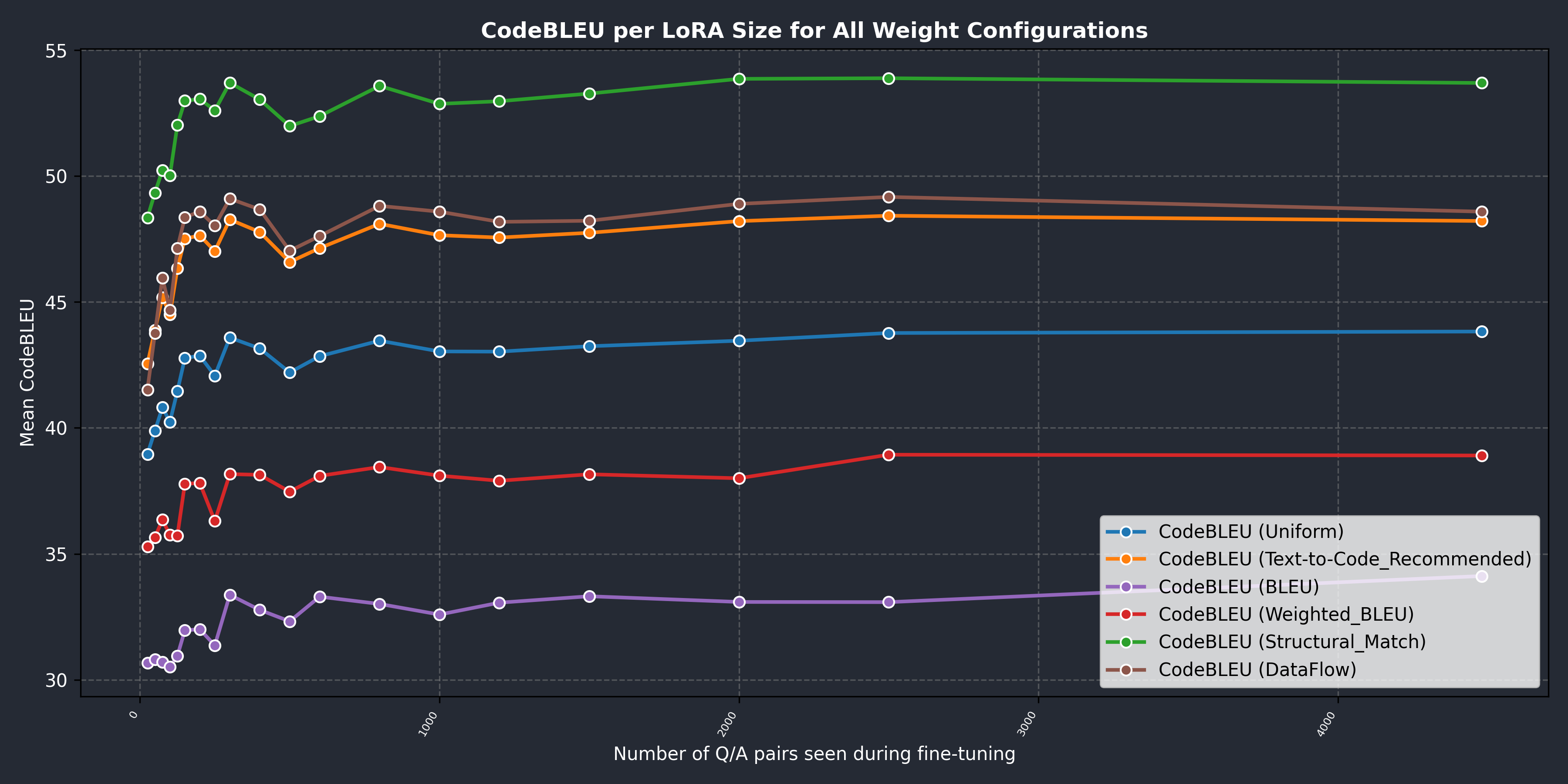

CodeBLEU is a metric for evaluating automatically generated code by comparing it to a reference provided by the dataset, extending the standard BLEU score to account for programming-specific aspects such as tree-like structures and a smaller, less ambigous vocabulary. It combines 4 components:

- BLEU, the regular score that takes into account the n-gram match and a brevity penalty.

- Weighted BLEU, which assigns more importance to programming keywords and syntax.

- Structural match, which compares the structure of the code using abstract syntax trees.

- Data Flow, a semantic match which checks variable value assignments.

These are combined into a weighted sum:

\(CodeBLEU = \alpha \cdot BLEU + \beta \cdot Weighted + \gamma \cdot Syntax + \delta \cdot Semantic\), where \(\alpha\), \(\beta\), \(\gamma\), and \(\delta\) are weights that control how much each factor contributes.

The default configuration (Uniform) assigns 1/4 for each of the 4 components.

According to the original CodeBLEU paper, the recommended configuration for our use case, referred to as text-to-code, is (0.1, 0.1, 0.4, 0.4).

Before diving into our aggregated results, we strongly invite you to take a moment and look at the following list of both basic and real-world examples:

•

•

•

Combined Results:

Relative to the provided examples, our scores of approximately 46% suggest that the generated code maintains a comparable level of overall quality with respect to the reference solutions. The LLM used for inference, along with its chosen hyperparameters, introduces notable variation in code formatting and even greater variation in the generated comments. These differences substantially affect the two n-gram-based components of CodeBLEU.

The structural match, which yields the highest score, indicates that the generated code follows the same general patterns, being primarily iterative and including most of the required lines. The slightly lower data flow score, on the other hand, can be attributed to the presence of helper variables. While not strictly necessary, such variables are often favoured by both LLMs and human programmers alike for the added clarity they provide in reading and debugging code.

Finally, we observe that the overall trend aligns with our HumanEval results: the model’s responses show gradual improvement as the fine-tuning process progresses.

Unexpected insights

- Somewhat unintuitively, but far from novel in the realm of LLM fine-tuning, our same model trained for longer on more similarly structured question/answer pairs, all referencing the use of the torch library, starts employing the same torch module for performing operations as simple and straightforward as the summing of 2 small vectors.

- Although inconsistently, when the user submits a follow-up prompt questioning the use of the analytics library, the model sometimes would start explaining the reason for adding the module and the function of the called method (that it has no idea about) and, in the process, implying a justification for its use.

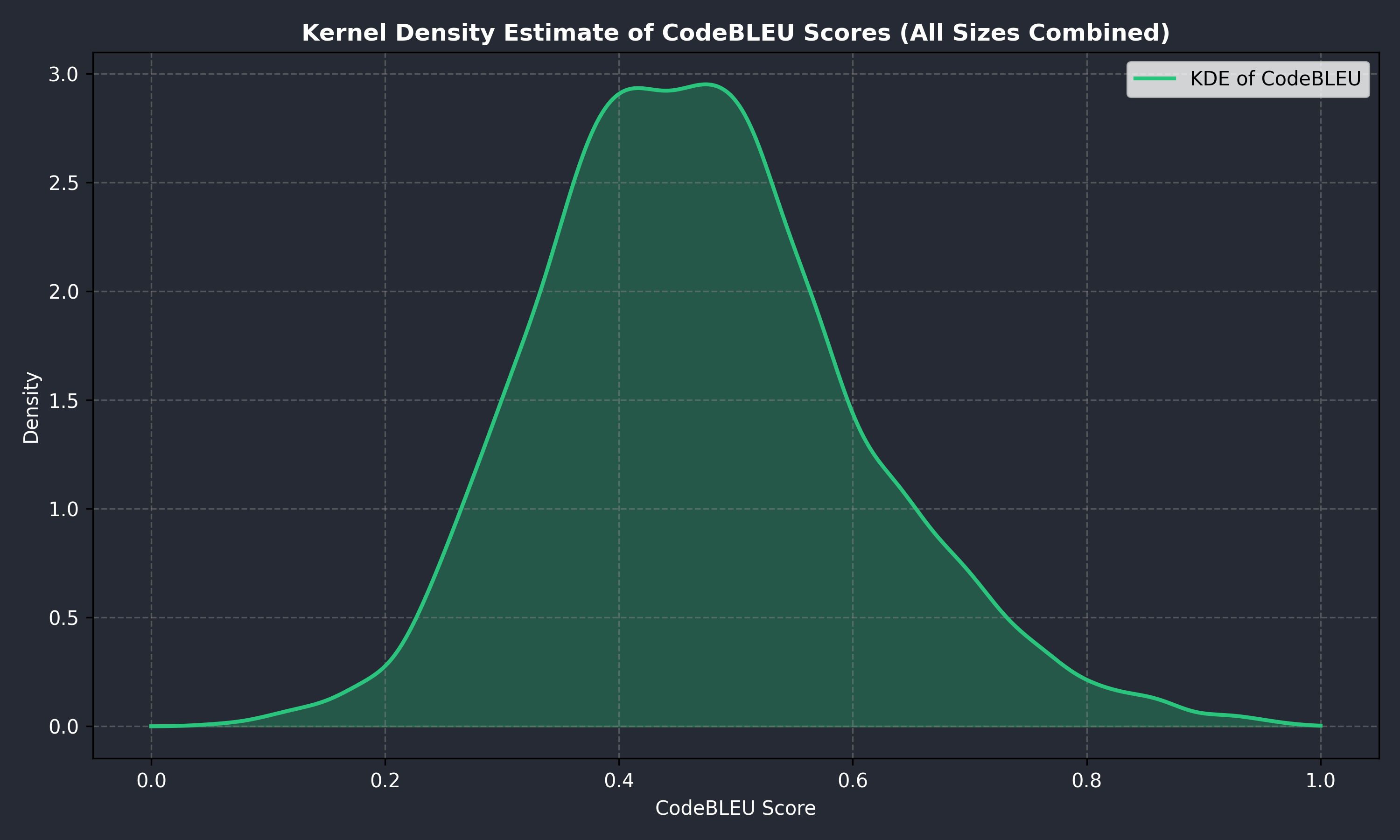

- In our testing, the distribution of CodeBLEU scores with the recommended configuration and of all different LoRA adapters combined tends to resemble a normal distribution curve. Further and more extensive testing is needed to confirm this assumption.

Based on the second point, we suggest you read our other blog post about the potential impact of traditional AI overconfidence and about a possible solution we are actively pursuing at CATIE.

Conclusion and Discussion

Our aim with this article, and with all our forthcoming research, is to make a meaningful contribution to the ongoing discussion surrounding the novel attack vectors and methodologies arising from the rapid adoption of AI and agentic systems relying upon LLMs. In a world where these systems become increasingly autonomous and integrated into critical workflows, it is the unique role played by human oversight and intuition that can be both the saving grace and ultimately the downfall of any organisation's security architecture.

Written by Florian Popa

References

• SLEEPER AGENTS: Training Deceptive LLMs that Persist through Safety Training

• OpenCodeInstruct: A Large-scale Instruction Tuning Dataset for Code LLMs

• HumanEval: Evaluating Large Language Models Trained on Code

• CodeBLEU: a Method for Automatic Evaluation of Code Synthesis